Chris Watt is from Scotland in UK, and he is a screenwriter as well as an author. He also has been a guest writer on my blog in this post about being a single dad. He went to film school and started off his writing career in film journalism from writing film reviews to interviewing talent from the films. Last few years, he’s been writing screenplays and seeing them produce into films and on the big screen.

He shares with me the joys of being a writer and the challenges. He talks about his favorite failure which I know is hard to imagine a failure being a favorite, but read on to see why his was.

Introducing Chris…

What do you love about your life right now?

I’ve found as I get older that I allow myself to be more optimistic about things that, in my 20s, I would have been far more aloof and glass half empty about. Generally, when you turn on the news in the morning, there are only negatives, but we’re part of a big world, and those stories, as tragic as they may be, or as angry as they might make us, are only a small percentage of what is happening around the globe, and I like to think that most us are simply trying to do our best, trying to find our little moments of contentment (which I think is far more important than happiness). To that end, the things that I love about life are fairly simple by most standards, but incredibly important to me living as fulfilling a life as I can. I love watching my daughter grow up, spending time with her, with a front-row seat to her becoming a young woman, with her own ways of expression, her own opinions and curiosities, and finding the things that will become her world for the next few years. And I love my work, the feeling of getting up every morning with a creative agenda, rather than the prospect of the many day jobs I had for the 20 years after leaving film school. I feel extremely lucky, and I try not to take that for granted. The world has become very fast, and I am maintaining my pace, which I know can be very hard for some people, especially if you live in a predominantly online world, as most people do now. I love the fact that while the world might seem to be falling apart, there are still people making splendid music, or taking a great photograph, or falling in love. Still managing to find the meaning in madness. These are the things that feel most important to me. It’s become fashionable to be cynical, and I did all that in my youth. As Cameron Crowe once said; “Optimism is a revolutionary act.”

You’re a screenwriter by profession, as well as the author of a novel, Peer Pressure, and back in the day you wrote film reviews and did interviews with talent. What do you enjoy about writing?

Writing acts as therapy for me, I think. Like anybody, I have had moments of real doubt, moments where I might not have made the right decisions or have been unable to figure out the right path to take, but writing has always been the element that allowed me to contextualize and explore my problems, and the problems of the world, with a focus that, particularly in my 20s, I didn’t have. To be able to take any issue, subject, or problem and create a character to be the conduit for figuring it out has been an immense help to me. And while it’s a lonely process, once you have created the world of your story, you can populate it with characters that will help you feel less isolated. It’s probably why my characters talk as much as they do. It drowns out the silence. In fact, I often joke that I’m jealous of my characters, as they are leading far more exciting lives than I am! So, I guess the answer to this question would be everything. I’ve always expressed myself creatively, but writing is what I seem to be best at, and without it, I would probably lead a far less rich or fulfilling life. It’s a luxury to live the life of an artist, in an art form that you love. I don’t find that kind of satisfaction anywhere else.

Was there a particular writer who inspired you?

There have been many writers who have inspired me over the years, and it would feel remiss not to place two categories here, separating authors and screenwriters.

I discovered author Nick Hornby when I was 15 years old, and it felt like a defining moment for me, reading High Fidelity and realizing that this sort of writing existed, writing that felt like someone was tapping directly into what it was like to be me. Hornby has that knack of mixing comedy and drama in a way that allows you to laugh out loud on one page and be on the verge of tears on the next. It’s very much in my wheelhouse, and while I have undoubtedly launched my career as a writer of darker material, I have always felt as if this type of writing, the dramedy, is best suited to my personality. Life is bittersweet, at its best, and I like to explore that in everything I do. It is, for example, no coincidence that certain reviewers of my novel were kind enough to call it Hornby-esque, which felt like the greatest compliment, as that is exactly the tone I was reaching for. To have Hornby also prove himself to be a fantastic screenwriter is also a wonderful gift to the world, and for a man who is so adept at exploring the male ego, he has also shown a remarkable knack for crafting fascinating female characters, something I try to do in all my work. At the same age, I also discovered Cormac McCarthy, who we sadly lost recently, and his writing always made an impression on me, as it explored a far darker sensibility, usually dissecting the evil men do, and a world on the brink of unspeakable violence, and while the outlook in most of his novels felt bleak, they always struck me as deeply profound. His books ache, as if they are grieving for a world (and in his work, specifically a country) that is fast disappearing, if it ever existed in the first place. At 15, I had never read anything like the writing that McCarthy gifted us, and I consumed every one of his books like an all you can eat buffet.

In terms of screenwriters, there are two key figures for me, who have really inspired and shaped the kind of writing that I aspire to in my own work. First, there is Bruce Robinson, who wrote (and directed) Withnail and I. As a writer, Robinson displays an almost novelistic approach to his narratives, but the dialogue is so vibrant, so fierce and so well crafted, that it allows the characters to jump off the page. He is also a terrific example of the life of a screenwriter, as he has only ever had a handful of his screenplays produced. It is astonishing to think that a screenwriter as talented as he is, with an Academy Award nomination (for The Killing Fields), a BAFTA award, and numerous credits, can’t get his own screenplays produced. It certainly isn’t lack of talent, as his screenplays are written with fierce intelligence and immense wit. It is a problem of the film business in general, and certainly a part of why the Writer’s Guild went on strike last year. The writer is just not valued enough in our industry. Without us, there is no industry. We create the stories, and Robinson has been creating stories for over 40 years but has very little in terms of produced work. But he is also a writer to his very core, and has written books while pursuing his screenwriting, and I find that hugely admirable, showing his versatility and talent. The second screenwriter is (already quoted) Cameron Crowe, who, much like Nick Hornby, is a writer after my own heart. Crowe started as a journalist, much as I did, although his journey is far more interesting, given he was writing for Rolling Stone at 15 years old. From there he jumped into filmmaking, and his screenplays are gifts. He, himself, has been inspired by the great Billy Wilder, who wrote or co-wrote some of the defining films of his time, including one of my all-time favorites The Apartment, and Crowe’s work has that same attention to the little details of life that make the characters relatable, laced with empathy, but also properly dramatic. Say Anything and Jerry Maguire, in particular, feel like perfectly contained love stories, but not just about male and female relationships, but about falling in love with life. They are optimistic, brimming with lyrical dialogue and they dare to wear their hearts on their sleeves, a kind of whimsical screenwriting that we see little of these days, in an industry that is becoming more and more preoccupied with franchise potential and announcing release dates before they even have a script written.

Do you miss interviewing talent?

I do, and in many ways, I have carried my enjoyment for interviews into my consultation work, where I work with screenwriters, all at different stages in their careers, helping them to reshape, refine and define their own scripts. Curiosity is a priceless trait and I’ve always been interested in other people’s stories, in how they see things. It’s one reason we need to embrace diversity within every aspect of our lives. What a boring world this would be if we all adhered to one point of view, one culture, one aesthetic. I think of all the great films, or songs, or paintings, that have been created from outside of what many people would consider the mainstream, and they are always the most interesting, as they give us an aspect of life that we maybe didn’t even know existed. Talking with the many filmmakers, actors, artist that I did over my time as a film journalist, was not only eye opening, but brought forth relationships with some of them I carry to his day. Because I interviewed, primarily, people within the indie film scene, now that I am a part of that scene myself, we are now colleagues, and I have never lost contact with most of them.

I gotta ask, do you have a favorite one?

The one that comes to mind is an interview I did with the filmmaker Maeve Murphy, a wonderful writer/director, who is just so expressive with her answers. The reason it sticks out is arguably because she is one of the people who has remained a good friend and has supported my filmmaking journey over the years. I interviewed her in 2016, when she was promoting her latest film, Taking Stock, and we kept in touch. She was even good enough to attend the premier of my first feature film in London, and we have exchanged work with each other over the years. These are the sorts of relationships that are priceless in this life. You simply never know what meeting a person is going to end up leading you towards.

Another good example of that is that, as a film critic, I often got to see the early work of filmmakers that would end up becoming hugely impactful in my life, such as when I reviewed a film called Little Pieces. That was a little indie feature film, directed by a man that I saw great potential in. That man was Adam Nelson, and five years after that review, having spent a lot of time in correspondence, he and I eventually ended up making a film together, The Mire, which we are currently prepping for release. To think that a feature film I wrote would be directed by a person who I only met through my time as a film journalist is testament to the notion of when a door closes, you go to another door. You never know what is on the other side.

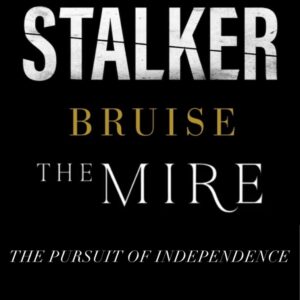

Some of your screenplays have now been made into films. For example, Stalker, which I love, and I don’t know if I will ever get into an elevator again. Thankfully, in my city, there aren’t that many buildings that have one. I also hope I never have a stalker either. How did you come up with the story line for this one? Also, how do you come with film ideas?

Haha! I’m glad you enjoyed it, if ‘enjoy’ is the right word for the experience we wanted you to have with that film. If I make people second thought taking the stairs over the elevator, then the film has at least resonated, which is all one can hope for. In fact, the idea for Stalker came from reality, when I found myself trapped in a shopping mall elevator between a second and third floor. Hardly the most perilous experience of my life, but for the brief moments I spent in there, I started wondering about the other people I was stuck with, and the experience made enough of an impression that it stayed with me for a few years, until I was working on ideas for the next project. The idea with Stalker was really to write something that could be produced under the covid restrictions that were about to come into force, meaning less cast, less crew, less location work, etc. So, I sat down and decided to use the elevator scenario and attached a narrative hook to it breaking down, which was: what would you do if you found yourself trapped in a space with your own stalker? That was the jumping off point to build upon that idea, and the story grew from there. I knew there was a powerful concept there, and the screenplay evolved into what it became, influenced heavily by the research I was already doing into domestic and sexual violence against women, for my other project, Bruise. Stalker works as a genre piece, but I also aspired for it to work on a more cerebral level, flipping the notion of violence against women and playing out a nightmare scenario in which the outcome becomes far less comfortable, and with a moral murkiness in which you question how certain punishments fit the crime. Ideas are like planting a seed. You start with a subject and then try to attach a good plot to that subject. For me, I start with the idea, then consider whose eyes I want to see this idea through. That’s how the characters come to life. If you’re going to, for example, make a film about flying, you give your protagonist a fear of flying, giving you a baseline conflict, or something for the character to overcome. That’s a simplistic example, but the principal works. You can break nearly any high-profile film down to bare essentials like this. The Mire was built this way, with the baseline of telling a story about a liar whose own lies trap him. You can find great hooks for stories from simply writing out a line like that, a logline, if you will, but one that is far more stripped back. The one stipulation I always have for any screenplay that I write is that it has to be a cinematic idea, even if it’s two people trapped in an elevator. A lot of screenwriters don’t use the medium enough. You need to write in a way that shows us why this needs to be a film, not a play or a tv show, etc. Show us why we will need to experience this on a 60-foot-high screen, surrounded by strangers. Screenwriting for cinema is unique in that you can play about with several perspectives or timelines at once, and yet craft it in a way that they all become connected, and I am obsessed with connection, be it through a line of dialogue, or a gesture, anything really. When I worked with the director of Stalker, we were extremely careful to make sure that any audience that wants to watch the movie more than once, will always notice something that they may not have noticed before, be it a look someone gives on a certain line, or what a prop is doing. For example, and this is not a spoiler, in Stalker, if people pay attention to the security camera in the elevator, they will see certain points at which it appears to be on or off, that was deliberately woven into the script to almost subliminally help move certain elements of the plot forward.

Is there any particular software you use?

I write on Final Draft software. In fact, I won the software in a logline competition, which is why it is my software of choice, which means I am both lucky and cheap! Final Draft is an industry standard, of course, but there is alternative software available. Really, you use whatever works best for you. It’s all about the process, and while I kicked back for years on getting screenwriting software, the moment I won a copy of Final Draft and tried it out for the first time, I realized how much more efficient I could be with how I used my time while writing.

Were you able to go on set for Stalker and give any input for the film?

Stalker was actually developed and produced during the pandemic, with every meeting taking place via zoom calls, so I could never get down to the set. Restriction had been lifted by the time production had properly begun, and I was invited down for the final day of the shooting, but I stayed away, as I had spent 120 days isolated from seeing my daughter, during the lockdowns, and I didn’t ’t want to lose any more time with her than I already had. I don’t think my presence on set would have done much good. As a writer, I feel my job is to deliver the best screenplay possible, and by the time day one of shooting comes, I’m usually on to other projects, so unless there is an enormous issue that crops up, my being there would be relatively useless. It wasn’t until our world premiere at Frightfest in London that I actually physically got to meet any of the cast or crew, although I met them all online over the course of the year we were prepping that film. A very surreal experience.

Your latest film is The Mire, which is currently gearing up for a release. That film made me think about how there are people in the world giving hope to individuals who feel hopeless, but in reality, these people are only there to take it all away. They’re kind of like wolf in sheep’s clothing. What was your inspiration for writing it?

It was very much that same sensibility of the wolf in sheep’s clothing. The inspiration for The Mire started about 10 years ago. I was working as a manager in a hotel and every year there was a gentleman, an evangelist preacher, who would stay over a series of weeks, and he used to sit in the lobby with his laptop, doing these one-on-one sermon sessions with members of his congregation, and it stuck with me, this notion of faith and belief structures in the 21st century. And I knew it was something that I wanted to write about one day. Our online lifestyle has, certainly in the last 10 years or so, become so much a part of how we live, how we socialise, how we worship and yet there’s a natural disconnect there, which makes it almost paradoxical, and you take all these elements and marry it to a group of characters, seemed to me to make up a good foundation for a story. The screenplay itself started in 2020, with the idea of a liar trapped by his own lies. When Adam Nelson and I had our first discussions about what kind of film that we wanted to make together, the idea of exploring a cult was the one that sparked us, so I went to my desk and opened my notebook of plots that I had no narrative attached to. I gave Adam three or four scenarios, but the one that stuck was the notion of a cult leader attempting to leave his fabricated community and having him caught by two of his higher up members. That seemed to me like a great hook. To play with this catch-22 notion of a man who could inspire these people to give him everything, but then to find that everything comes at a price. I had read a lot of books about these communities, particularly Jim Jones of the Peoples Temple and also Marshall Applewhite of the Heavens Gate community. But I had also read about Manson and that notion of the loudest voice in the room, but interestingly most of the literature I was reading had a recurring element: the survivors’ perspective. So, I knew I wanted to write about every aspect, using two follower characters as a means to show the potential human cost of this type of manipulation.

Have you thought about directing a film or even acting in one?

I often get asked this question, but honestly, directing is not a discipline that I feel I would be well suited to. In film school, I directed a few shorts, but nothing that ever really gave me the impression that I would be any good at it. I like to make it work on the page, and I enjoy collaboration with directors, to facilitate their vision for my story. That is interesting to me to see my story through the eyes of the person who will make it a reality. So often the relationship between writer and director, and particularly producer, can be misconstrued. I’ve felt very lucky that the directors I’ve worked with, like Steve Johnson (Stalker), Adam Nelson (The Mire) and Mo O’Connell (Bruise) have been willing to even have the conversations that sometimes need to be had, as many writers, I know, never get that opportunity. Obviously, it won’t always be like that, so I’m enjoying the collaborative process while it lasts. Acting is out of the question. I simply do not have the skill or talent for that, which, interestingly, all bleeds back into the writing part of my brain.

I actually started out wanting to be an actor, doing school plays, and even auditioning for a couple of drama programs in my final year of secondary school. But I had also applied to some film schools, as I was fairly certain that I would never be a good enough performer to get anywhere with acting. And I was right. Seeing other actors perform their auditions before I did, it was clear who would make the grade and who wouldn’t, and I think that any talent I had for performance was better suited to creating characters on the page and leaving it to far better suited talents than mine to make a reality. I’m in awe of actors, and it has been a real pleasure to see professional actors work with my material, as they bring their own inflection to every word, create nuance and backstory that I would never think of, and they make the character their own. Sophie Skelton is a great example of this.

In Stalker, Sophie is asked to play a fairly complex character and the dramatic shifts are quite large within my screenplay, given the restrictions of the setting of the story, but seeing how she maneuvered the arc and the changes of the character of Rose really floored me. We had all seen what she was capable of from Outlander, but this character was so far removed from that part, and she really went for it. The Mire gave me that same experience, and that is a pure character piece, that demands a lot from the actors, who all delivered under extremely pressured constraints. The Mire was filmed in seven days, and it is a dialogue heavy piece, so the fact that they could give so much of themselves to those parts is testament to their and the crew’s dedication.

There are challenges and joys in our career and lives. What have been the joys and challenges as a writer?

The challenges make the work fun and worthwhile, for me, so in a way, they are also the joys. With every project I start, there has to be a reason that I chose to pursue it. With the novel Peer Pressure, the challenge was to see if I could write a story with a predominantly female perspective, with the two main characters being a mother and daughter. To write female characters who don’t feel like a male has written them. With Stalker, it was about the challenges of setting an entire drama within one confined location, and that was really fun to play with, almost like a stage play that could then utilize the medium of film to allow the walls to creep in and the characters to become more intense. I wrote a short film called Bruise, in which I challenged myself to tell a story with no dialogue whatsoever, and from that challenge I came up with the idea of writing it to be interpreted as a dance, which worked beautifully when it was finally produced, with our main cast made up of contemporary dancers whose movements reflected the journey of the characters. That was also a script in which I was exploring some harder subject matter, dealing with domestic violence and sexual abuse, and with that sort of experience, the research proved very tough to get through, but we were extremely lucky to have some amazing support networks willing to talk to the filmmakers about the experiences of survivors and victims. Don’t get me wrong, the day-to-day challenges are often incredibly frustrating. Screenwriting, and in fact ANY writing, is far harder than people might think. Screenwriting has so many ways to trip you up, so many holes you can fall down, and shifting just one element can make the house of cards collapse.

I am in development on at least three projects right now, but the film industry, especially in the U.K. moves incredibly slowly, so finding those script jobs that are going to allow you to wait, are vital. I’m very lucky that my work as a script consultant allows me the freedom to write for myself, without worrying about the wolf at the door. But the joy comes from the doing. Once I sit down at the laptop, with the story that I want to tell locked and outlined, there is no better natural high than letting the words out and seeing where each story or character will take me.

We all have experience failure and sometimes success follows it. Do you have a favorite failure?

That’s a brilliant question! I’m a firm believer that we have to embrace our failures, because, as I mentioned before, the door that closes makes you go to another door, and who knows where that might lead? My favorite failure is connected to a screenplay of mine that was optioned by a film producer. On the same day I signed the option, a filmmaker who had also read the script contacted me and wanted to make it. Of course, the contract had been signed, so it wasn’t to be, and that filmmaker then made a film that would become a huge success and won a few BAFTAs, while the script I had written, sat in development for two years and never got made. Although I am now looking for producers to have a look at it, as the rights are now back with me. Now, in any other circumstance, one could consider this a missed opportunity, and perhaps it was, and a classic case of bad timing, but, crucially, that script option led to me having my first ever produced feature film, and through that I met Steve Johnson, who has been the most important element of the last four years of my career, and if that screenplay had gone with the other filmmaker, I would have never met Steve. This business can be hard to move through and negotiate, so having people like him, who have your back, and whom you can do the same for, can be invaluable. I simply stepped through another door, and it has led to a career, regardless of which project it is that launched me.

Is there any advice you would give to someone who wants to pursue a career as a writer /screenwriter?

First, I wish you nothing but the best of luck. It’s a hard, difficult road. But as cliché as it might seem, the only advice you can give is to never give up. It took me 20 years, from graduating film school, to attending the premiere of my first produced film, and there was a whole life in between, including a marriage, divorce, becoming a parent, a handful of relationships, and crucially a multitude of day jobs, but they are all part of the journey, and you need to utilize all that frustration, all that aspiration, and channel it into your work. You will spend a lot of your time writing just for you, but the more you write, the better it will get. I would also say that, when it comes to WHAT you write, create within your own life experiences. Cinema is a dream factory, and yes, there will always be a need for spectacle, but the best drama comes from our own behavior, from human conflict, and the more personal you can make it, the more it will resonate. Relatability is the key for me. If you give me a character or a situation that I can relate to, then you can take that story anywhere, from a family sitting around a dinner table to a galaxy far, far away. I always think Star Wars is a good example to use. Yes, it is full of spectacle and spacecraft and aliens and all of that, but at its heart, it is about a young boy taking a step into adulthood. That is the relatable element, and that makes the story endure, allowing the narrative the license to do whatever it wants around that core ingredient. It’s a fun exercise to play with any movie you watch. Take any film and try to grasp what the relatable element is, and every wonderful film should have one.

If you could have a gigantic billboard anywhere with anything on it, what message would you want to convey to millions? What would it say and why?

Ha! I don’t think I would want any ideal or message on a gigantic billboard. That would give the suggestion (and advertising works on this principal as well) that whatever the billboard says is probably worth listening to, and as we know, that is almost never the case. I actually think we need fewer billboards, and more original thinking in the world, in the places where it matters. The billboard is an interesting parallel to what The Mire is about, the notion that if you say something loud enough, or with the biggest platform you can find, then many more people will follow its guidance than not. I know also that I have simply refused to answer the question, by, ironically, hiding behind my own ideas, so in the interests of balance and to show I’m not an overly serious grouch, I would have the billboard say: What Are You Looking At?

Describe yourself in one word.

Patient. In this business, you need to be, as there are so many months, sometimes years, of projects sitting in development hell. I’ve been lucky to have two feature films I wrote, produced back-to-back, but that is almost completely circumstantial, as all productions halted during the pandemic, and so both started back up at the same time. That is not the norm, and I am now in a position where I am lucky enough to be able to work, but on projects that may never see the light of day. That’s the screenwriter’s life though and much like Bruce Robinson, you will write many scripts in your lifetime, but you must be prepared to have most of it go unseen. But it’s not just about being patient with the work, but being patient with life. I’ve had my fair share of knocks over the last 20 years, but I’ve kept going, thanks to some remarkable people, but also by giving up in pursuits of things that my younger self thought I wanted. These days, I’m simply laid back and I find it far easier to deal with any issues by simply sitting down with a piece of paper and dissecting the problem. More often than not, people worry so much that they never get to that stage of simply sitting down and looking at the problems directly. Every problem has a solution. Keeping calm and being patient is the key to solving it.

In a past interview, you shared with me three fun facts. One of them is you collect first edition books. Can you share with me some titles of your first edition books?

I have all of Nick Hornby’s work as first editions, with some of those signed as well, with my pride and joy being the first of High Fidelity, which is unquestionably my favorite novel. I am lucky enough to own a few first editions of Cormac McCarthy’s books too, including No Country for Old Men and The Road. The biggest issue with first editions is that they take up a lot of space, so these past few years I’ve been whittling down my collection to the books I know I will read again, before the bookcases begin to give up. My problem is, I’m also a sucker for those lavish coffee table hardbacks, the kind that companies like Taschen produce, but some of those are literally the size of a coffee table, and extremely expensive, so I have to be more disciplined with those.

I gotta to know some more fun facts about Chris. Can you share with me three fun facts about you?

I don’t know if any of the facts about me would be considered fun, but I’ll give it a shot.

So, fun fact one would be related to an earlier question about acting, as my first experience of working on a film set was at 12, when a film crew came into my hometown and were looking for background actors for their production. I did a day’s work on a film that starred Greta Scacchi and Vincent D’Onofrio, called Salt on Our Skin and my scene was eventually cut out of the finished film. That’s a good place to start in the film industry: on the cutting room floor.

Fun fact Two: I don’t drive. Is that fun? I’m not sure, but I have never been interested in cars, or enjoyed the experience of driving. I did the lessons, but never sat for a test. I think driving is extraordinarily dangerous, so I prefer to leave driving to people who do it for a living, like taxi drivers, bus drivers, etc. I spend a lot of my time in cities, so it’s never really been an issue for me, and I’m also not the most coordinated person in the world, so I can only assume that if I was in charge of a large chunk of metal, on the road, it would end in disaster, so I have no intentions of every putting myself, or other people in that position. And from what I’ve seen, there are far too many people on the roads that treat it like Grand Theft Auto. I trust myself behind a steering wheel, almost as little as I trust other people.

Fun fact Three: I’m a hobbyist photographer. I don’t think I have much skill for lighting, but composition and framing I’m quite competent with. I think it’s an offshoot of all my years of watching and studying cinema. I have a good eye for capturing an image, because of that. I particularly like symmetrical elements and shapes, which I’m sure come from Kubrick being my favorite filmmaker.

I love ending the chat with a quote. Do you have a favorite quote or saying that has inspired and motivated you in your life that you can share with my readers?

I have a favorite quote from the filmmaker John Cassavetes, that I think about constantly, especially when I’m having my days of doubt about what I do for a living. He says…

“Say what you are. Not what you would like to be. Not what you have to be. Just say what you are. And what you are is good enough.”

It’s advice to live a healthy life by. Owning it, knowing who you are and that regardless of all the noise, regardless of who is doing what on Instagram, or what kind of life other people seem to live (which is almost always a lie), what you are doing is fine and who you are is exactly who you need to be. To quote a character from my screenplay, The Mire, the biggest issue humans have on this planet is that “We think we matter” and yet in 100 years, or a couple of generations time, we don’t. So why we get so hung up on the awful things that we do in the name of war, power, money, I will never know. I choose to lead a fairly simple life, where those I care for come first, and all I can do as a writer is hope that some portion of my work will last and allow others to consider certain subjects and certain ideas, even after I’m long gone. And if they don’t, I’m fine with that. I said what I wanted to say and tried not to hurt anyone in the process. And I tried to enjoy it while I was here.

Thank you for reading my interview with Chris. He has given wonderful advice for writers as well as sharing his experience as a screenwriter. One of my take aways, is to never give up. The other is to be patient because good things take time and often what we think is a misdirection is actually the right course.

Follow Chris on social media.