My newest chat is with Adam Nelson of Portsmouth, England. He’s a film director as well as a poet. He shares with me the joys of directing and how they outweigh the challenges. He loves the creative process of it all. We also talk a little about Stanley Kubrick who produced and directed The Shining among other films.

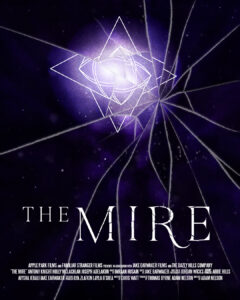

One of my favorite parts of the interview is where he talks about his vision as a director for the film, The Mire, written by Chris Watt. Another part I enjoyed is where he shares his favorite failure with me, and I was surprised by his answer.

Introducting Adam…

What do you love about your life right now?

My feature film has recently been released internationally and will soon be released in the UK, along with a short film we’re preparing to release. I have a day job that I enjoy, when 70% of the UK film industry is out of work is a blessing. I’m about to launch a Substack where I’ll be writing about my love of film. Outside of that, I’m lucky to be able to do things I enjoy.

Was there anybody in particular or a film that inspired you to become a director?

Becoming a director was actually more of a necessity than any one person. I’d had a go at making films when I was younger, but it never felt like something I would get to do. I come from Portsmouth, which is a naval and industry-based town (or was when I was growing up). People like me rarely got to make films. I originally wanted to teach and at one point wound up having to teach filmmaking. Invariably the young people ask you what you’ve made, so I made my first serious short film in order to show that I could make one for the young people I was teaching.

Your first feature film you directed, Little Pieces, you also were the screenwriter too. I imagine you write and direct films you’re passionate about. What inspired you to write the film and direct it as well?

Logistics was the main reason. I knew how much money I could put together and what I had access to. So in writing the script, I could stick to those boundaries. It also allowed me to explore some things that I didn’t necessarily want to confront directly in my life. I think, in a way, that it was detrimental to the film overall to do that. The film is very earnest and comes off a bit overdone in many places, but it was worth doing just to have learned the lessons during the process of taking a feature film from concept to final product. And the ice rink scene is still the best example of the filmmaker I can be when I get out of my own way.

As I was doing research for our interview, you shared something on Linked In that was very interesting. You wrote, and I quote, “I tell stories about lost souls looking for a home.” How were you drawn to that subject about lost souls?

I don’t really have a concrete answer for this. It’s just something that I’ve seen come up in all the work I do in terms of the stories I’m drawn to when I read scripts others have written or when I sit down to write myself. I write a lot, not only screenplays but short stories, poems, and prose as well. In all of my written work, there’s a genuine sense of people who don’t fit in and don’t know how to. I think it’s because I often feel separate from the people around me. I don’t always understand people and why they do the things they do. Maybe I’m trying to explore that part of me through the stories I choose to tell. I don’t know.

Part of the film, The Mire, which was written by Chris Watt and directed by you, is about lost souls looking for a home. I loved it and enjoyed the psychological thrill of it. By the way, I can relate to it, and I’ll share that with you later. What was your vision regarding directing the film?

From the beginning, I was certain that I didn’t want to create a movie about religion. I felt like that would be taking the easy way out. I’m not a religious man, and I have my criticisms of it, but I also know plenty of people who benefit from their faith. What I found far more interesting was the idea of how people can manipulate others through religion, and how some people will fall for some pretty outlandish ideas. The things Joseph Layton speaks about sound insane but, in the world of the film, many people have fallen for it. My day job involves working with young people and we all have to take what’s called PREVENT training, which focuses on how to stop young people being groomed by terrorist or hate groups. What you come to notice through all the case studies is that those who get pulled in are very vulnerable and feel very isolated. During the Covid pandemic I noticed very similar things, people as a whole felt very scared and isolated, and I found people who I always felt were quite intelligent and reasonable, suddenly believing in some really out there stuff. That was a far more interesting angle on the approach than just religion.

I also wanted to make something very commercial because, at heart, I love commercial films. I grew up watching commercial films and so that’s the route I want to follow in the long term.

For those who don’t know, and I’m still learning about the process myself, how did you end up becoming the director of The Mire? Did you read the script and reached out to Chris?

During the early days of the pandemic, I had been thinking about how best to utilise my suddenly open schedule. I had a conversation with a man called Clive Frayne and he suggested making a really contained film over a short period of time to best handle the rules around filmmaking and not take up too much of everybody’s time.

Chris and I have known each other for a while via Twitter and at around the same time I had the conversation with Clive, I offered to read Chris’ script Fr(e)ight, which became Stalker. I thought I could make Fr(e)ight and set about sourcing a budget, which is where a local contact set me up with the people at the Kings Church where The Mire was shot. I fell in love with the building and so when Chris sold Fr(e)ight to another production but offered to write me a script for me to make; I sent him the floor plans to the church along with a set of photographs and said I wanted to make a film there. We had a chat about things we could make a film about in that setting and we settled on a cult. Thus The Mire was born.

Stanley Kubrick said, “The idea that a movie should only be seen only once is an extension of our traditional conception of film as entertainment rather than art.” Do you agree with Stanley, and what’s your thoughts on his quote?

I’m not sure I do, mainly because the films I revisit the most are films that fit more so into the entertainment category than the art category. Entertainment brings people comfort and so I think people are more likely to revisit entertaining films. That said, it’s also perfectly valid to revisit more artistic films to see what else is there, the same way I would re-read a literary novel to see what comes up. I’m not going to say Kubrick doesn’t know what he’s talking about with this, but he was approaching filmmaking from a purely artistic perspective. All he wanted was what was best for the film. I adopt a more neo-formalist approach to film analysis. I take each film on its own merits, whether it’s more art or entertainment, because I feel it’s somewhat unfair to compare the two as they serve different purposes.

What are some challenges and joys of directing?

The challenges for me are managing my ambitions in line with my budgetary restraints. There are so many films I want to make, that I just can’t right now because I can’t find the funding. It’s easy for filmmakers to sit and complain about not having the money. I don’t like to add to that crowd; it is a problem, the UK film industry is pretty much on its knees and no one seems to want to do anything about it. I’ve accepted I have little access to money, so for me it’s far more about tempering my ambitions within that.

The joys far outweigh the challenges. I love the creative process. Collaborating with people is something I love, including writers, actors, editors, composers, and everyone involved in the process. I love taking my idea, or the writer’s idea, stamping my vision on it and then explaining that vision to others. During that process, other people bring in ideas and share them with me and I get to act as a filter for a wide range of fun ideas. Not all of them work, but it’s great fun to hear them and play with them. Then crafting the film in the edit, collaborating with the editor as we take what is essentially a mess and mould it into the final film. Finally, it’s a pure joy to share the film with audiences. I’ve had the pleasure of seeing The Mire with three audiences and there’s a moment towards the end where the audience always reacts the same way. It brings me joy every time.

Is there anyone you look up to in the industry?

There are filmmakers I admire and am influenced by, but I’m not sure I look up to anyone as such. The man who encouraged me to really have a go at filmmaking after seeing my first short film has, sadly, passed away now. His name was Simon Westcott, and I definitely looked up to him. He was a mentor both in education and filmmaking. He always knew the right thing to say when I was stuck. I knew him and I worked with him, so he’s the type of person I looked up to. I find it hard to look up to people I don’t know.

Is there any advice you would give to someone who wants to pursue a career in the entertainment industry as a director and screenwriter?

I think the best advice I can give people is to ignore a lot of the advice that’s out, especially when it comes to screenwriting. There’s a lot of information online about how best to write screenplays and I think a lot of it is rubbish. It’s all geared towards placing in competitions, many of which aren’t part of the industry but are more industry adjacent. The amount of scripts I read that come across dull and boring are incredible. People leave out any sense of flair or excitement and it’s because they’ve been told to leave out anything that could be unfilmable or would be ‘telling the director what to do.’ What you’re left with is very little visual writing and a lot of dialogue. I always tell people to read produced scripts and imitate what they find there, whilst most tell writers not to do that because the pros can get away with things, spec writers can’t. It’s rubbish. 99% of writers fail, so why do people insist on following the same advice as those 99%? I was lucky enough to be hired for a gig where I got to work with a script editor and the more I took her advice about that project and worked it into my writing, the lower I placed in screenwriting competitions. That’s my anecdotal evidence that most screenwriting advice online is rubbish.

Directing is a bit different because the job is about communication and answering questions. It’s about translating your vision for the film to everybody else and then staying on schedule and on budget. I think there’s a temptation by younger directors to make the job bigger than it actually is. It takes on an almost mythic feel when, in reality, a lot of directing is just answering questions and staying on task. My advice would be to direct something small and see what works for you. Oh, and make sure you wear comfortable shoes.

We all have experienced failure and sometimes success follows it. Do you have a favorite failure?

Little Pieces, my first feature, is my favourite failure. That might surprise many people because the film was somewhat successful, touring the world and getting nominated for one pretty big award, but it never did what I hoped it would do. There are plenty of reasons for that, though the main one is that I wasn’t ready to handle something on that scale. Regardless, there were plenty of positives to come from it – I have a great working relationship with Finnian Nainby-Luxmoore, who has been in all but one of my films since making Little Pieces.

Who are your biggest supporters?

My family and friends. I’ve been really lucky that they’ve been willing to support me as I make films and never have they called me crazy.

If you could have a gigantic billboard anywhere with anything on it, what message would you want to convey to millions? What would it say and why?

I genuinely do not know how to answer this. I honestly think that I’m the last person people should listen to.

Describe yourself in one word.

Tenacious.

This is one of my favorite parts of the interview. Alright, Adam, tell me three fun facts about you. You can share something outrageous if you dare.

Unfortunately, none of these are outrageous. I don’t live an outrageous lifestyle. As for facts:

- I write poetry and I am arguably a more successful poet than I am a filmmaker.

- I have everybody involved with my films sign the front of my director’s script in the vague hope that one day, one of them will be famous enough that I can sell it and make some money.

- I’m a huge fan of rock and heavy metal music and I really miss going to concerts all the time.

They may not be as fun or exciting as other people’s, but I prefer to live a quieter life overall.

I love ending the chat with a quote. Do you have a favorite quote or saying that has inspired and motivated you in your life that you can share with my readers?

“For fuck’s sake Adam, just bloody well get on with it.” – Simon Westcott, to me when I was dilly-dallying about whether or not to try and make Little Pieces.

Thank you for reading my chat with Adam.

Go to this link on Tubi to watch The Mire.